For the last seven years, I’ve lived near the beach, beside the Del Rey Lagoon in Playa del Rey, California. The lagoon is 1/4 mile long and about two blocks wide. The immediate area is salt water and fresh water from some of the last remaining wetlands in the US. Historically, there are over 300 species of birds recorded in the area. Researching piece about the opening of the restored freshwater marsh in the contiguous wetlands just east of the lagoon found 150 species of birds in a single afternoon foray.

In the lagoon itself great blue herons and egrets fish in the late afternoon and perch in the trees like Christmas ornaments in the morning. There are also migrating flocks of coots, local grebes and loons, gulls, geese, sandpipers, cormorant, tern, sparrows, flycatchers, warblers and an occasional Kingfisher. And lastly, there are sparrows, flycatchers, warblers, mockingbirds, and other songbirds. There are also red-tailed hawks, American Kestrel, Northern Harrier, White-tailed Kite large flocks of Black-bellied Plovers in the winter.*

The birds I know best are the resident flock of 60 or so mallards and the seven Toulouse geese brought there as goslings to beautify the area (as if it needed more bird species!).

Most of the residents I know on sight. And the ones I never miss are the pet pekin dumped in the lagoon. People unwittingly think they’re doing a good deed letting their bird loose with other ducks to live a wild life. But pekin are bred for food and don’t know the alarm cues the rest of the birds do. Mostly they get nabbed in the first month by dogs off leash or nocturnal predators, like raccoons and the occasional red fox.

I keep an eye on the pekins and make sure they’re okay and getting enough to eat. Being pure white, they’re hard to miss. And they tower over the mallards like Arnold Schwarzenegger over a toddler.

I rescued a little runner duckling from the lagoon in 2007 that I named Dewie.

She lived in my carpeted apartment for three months while I sought her a perfect duck home. That story became the documentary film, “Little Miss Dewie: a Duckumentary.” It won two awards and was seen in 23 film festivals around the world. I did end up finding Dewie a great home and she is now happily married to Hercules, the biggest pekin I’ve ever seen. The couple lives with her mother-in-law about 45 minutes east of LA. Their first offspring, Helena, hatched in the summer of 2010.

After Dewie, there was a drake (male) pekin I’d been keeping an eye on since he was dumped by his owner one night. He was doing well, surprisingly so. Then one day he was laying on the embankment which wasn’t unusual. That’s what all the waterfowl here do to sun themselves. But when I put out a bag of food he couldn’t get up. Turned out he had a big boil on his leg. I took him to IBRRC.org, a waterfowl rescue & rehab, & the vet said he needed to be put down. I wouldn’t let them do it for two hours. I made them take an x-ray & I called other vets.

My avian vet was out of town for two days and then had surgeries booked and the IBRRC vet said the drake wouldn’t last that long. He needed immediate treatment. I suggested taking the leg off but they said I’d have to somehow keep him off the leg and change his dressings twice a day or more, to keep the wound clean at all times. So as soon as he pooped and stepped in it, I’d have to undo the bandage, disinfect the wound, and bandage him up again. That would be near impossible to do on my own, it would need to be done several times a day because there is no more prolific a pooper than a duck. And, he was big with a lot of fight in him. It was hard to keep my arms around him when I took him to the car. They kept saying it would be a full time job. I knew it would be a nightmare.

Even so, I didn’t care; His life should not be determined by my convenience. I told them to just remove the leg but then they told me there was only a 5% chance it would be successful even if I did everything perfectly because it was so far gone. And even if it were successful, the pain would be excruciating for him between then and the weeks before it healed.

There was nothing wrong with him. He just couldn’t walk on that leg & he was in pain. He was perfectly healthy. He was alive and energetic and I couldn’t see putting him down but I did it anyway. I brought the x-ray to my vet when he got back because I couldn’t live with myself. He said the same thing they did and if there was a way to save him, my vet would have said so.

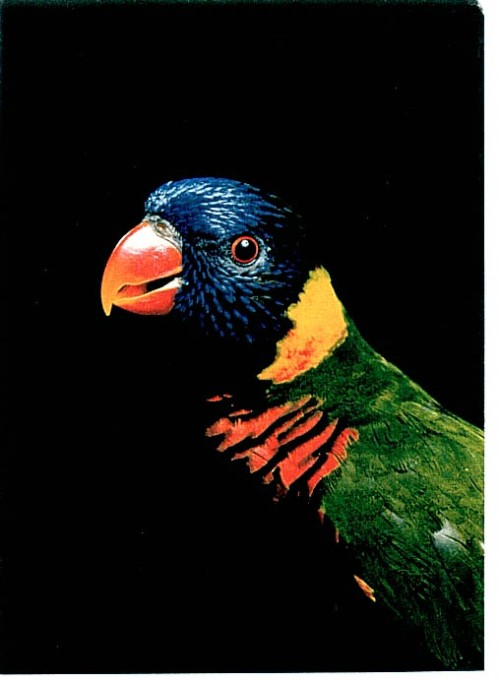

I have struggled with this issue of what to do in medical emergencies with parrots since Mango died. Mango was my rainbow lorikeet companion of ten years. He was the one who raised my consciousness about parrot issues, in the wild and captivity. Were it not for him, I would not be writing this now or would I have written two books on parrots and numerous animal welfare features and exposes’ for newspapers and magazines.

Mango:

When Mango first showed signs of something wrong, I called my vet and started him on antibiotics. When he stopped eating three days later I ran him to the vet’s office. Had I known how far gone he was with aspergillosis (tests didn’t show it and it wasn’t confirmed til the necropsy) I would never have made him undergo all the prodding and testing at the vet’s office which was horrible for him, especially since he couldn’t breathe and was so weak. All he wanted to do was sit on my shoulder, nestled in my neck, while he withered away. Instead of dying with me at home in a quiet place, feeling safe (as safe as anyone can feel in that situation). He died in pain, alone in a fish tank, under florescent lights, in a sterile surgical room. And envisioning that makes me cry as I write this and it’s four years later. I would never do it again.

After Mango died I got calls to adopt another lorikeet. I wasn’t ready but I began hands-on rescue work helping these unwanted or rescued birds get into zoo exhibits around the US. That was how I ultimately adopted ZaZu, another rainbow. I’ve already decided, if he gets sick and there’s a good chance what he’s got is likely to be fatal, I won’t bring him in. I won’t subject him to that and take the chance of him having the death Mango did. Having a gentle death means something. It means a lot to me, as a guardian and friend, to provide that.

ZaZu:

A pigeon rescuer I respect said I had to “bet on Mango’s life, not on his death” so I did the right thing and I should do it again. But it’s a dilemma I cannot come to terms with. I know it’s on a case by case basis and whatever kills ZaZu will have its own scenario. It’s a tough decision and I no longer feel that going to any lengths to save a bird is a good choice if there’s a good chance it won’t be saved.

What do you do in cases like mine with Mango. How often is an illness serious enough to tell that racing to the vet is not going to help, or there’s not a lot of chance the bird will recover even if you do? And how often to you make the decision to give hospice care instead of invasive medical attention?

I’d like to hear your thoughts on this, mostly moral, issue.

Thanks, Mira

*Additional species sighted from research by Bob Shanman, Birds Unlimited, Torrance, CA.

Bob conducts guided birding tours of the Ballona Welands area and others around Southern California. Contact him at [email protected] if you’d like to join him.